How I Categorize Tactile Switches

Share

While I have absolutely no hard data to back up this claim at all, I’m willing to stake a good amount of money that tactiles are the most popular type of switches for people new to mechanical keyboards. Whether they come in the form of already built-in Cherry MX Browns, or incredibly hyped frankenswitches for a custom build such as Holy Pandas, Zykos, or BCPs, they all share the singular characteristic of providing a noticeable, distinctive feedback somewhere between the start of a keystroke and the bottom out. However, that is about where the similarities end. Completely disregarding differences that may arise between two tactile switches as a function of their stem length, material, or manufacturer, the tactile bumps in and of themselves have enough variety to make each tactile switch really stand out from the rest. With respect to this point, force curves do a solid amount of work in denoting the hardline, numerical differences between tactile switches, though admittedly those aren’t exactly everyone’s favorite to read about. So, for those who are not as into extra math, numbers, and graphs with your free time hobbies, here’s how I conceptualize tactile bumps when I’m exploring a new tactile switch for the first time.

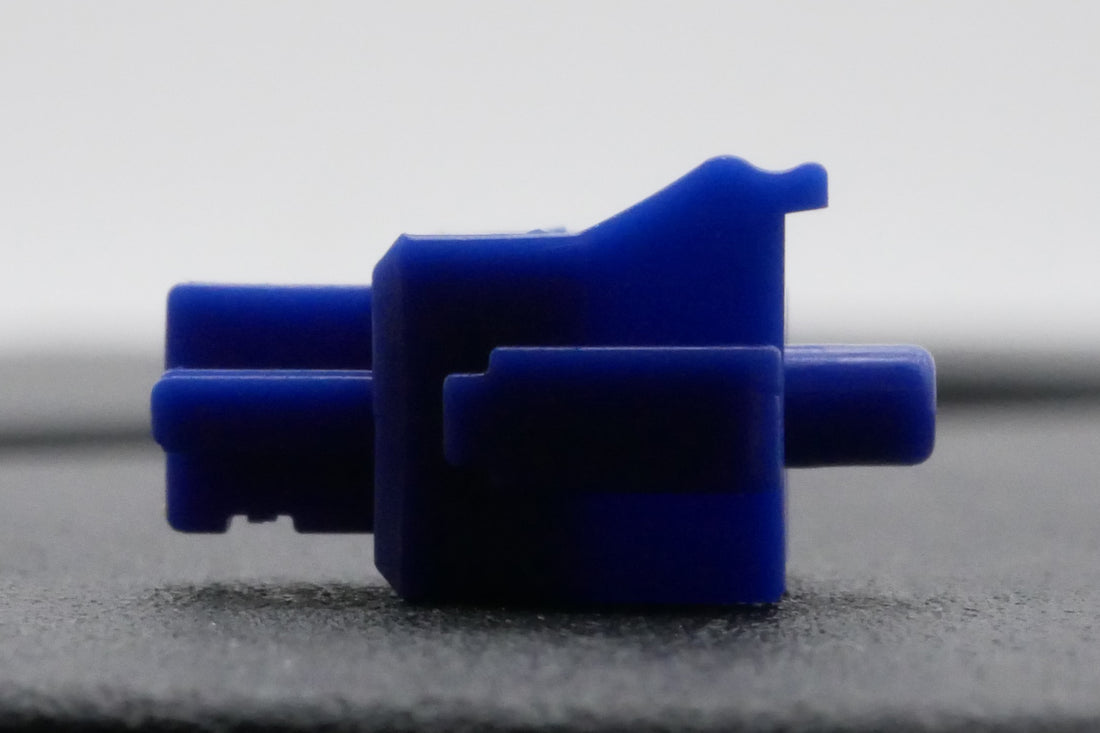

Figure 1: Behold, tactility! (Stem profile from Momoka Shark)

The first thing to really hammer home when attempting to conceptualize and compare tactile bumps in switches is what actually is a tactile bump and what causes them to occur. Tactile bumps are a direct result of the interaction between stem legs and leaves as a switch is pressed inwards. Starting without contacting at the top of the downstroke, as the switch is pressed inwards slowly, the leaves make contact with and effectively trace the shape of the stem leg, starting at the bottom and working up until they finally disconnect again and the bottom out is reached. Given that the legs in any given tactile switch stem are curved, as can be seen above in Figure 1, this causes the leaves to push in and out throughout the stroke and vary their pressure on the stem. This variation in force on the stem is ultimately what we perceive as a ‘tactile bump’. As you might have been able to put together based on that description, the combination of the shape of this bump on the stem legs and the shape of the leaf in any given switch is what produces a particular tactile feeling. But when it comes to describing tactile bumps and comparing them against one another, the following are the two big metrics I like to discuss:

Tactile Bump Strength

Figure 2: Range of tactile bump strength going from weak to strong. (L-R: Cherry MX Brown, Naevy V2, C3 Kiwi, and OG Holy Panda)

Tactile bump ‘strength’ is the term that I use to effectively describe the peak tactile force of any given switch relative to its baseline linear force. While you could attempt to directly compare the singular peak force between two switches, often times switches which feel ‘stronger’ have a peak force that is further away from its baseline, linear force than a ‘weaker’ switch. That is to say that a switch with a 40g linear travel leading up to the bump and a 75g tactile peak bump force would feel stronger than a switch with an 80g linear pre-travel and only an 85g tactile peak force. It is the difference in force from baseline that you feel as a result of the tactile bump which lends to the tactile ‘strength’ of any given tactile. While the range of tactile bump strengths shown in the image above should give you an idea of what “weak” versus “strong” tactile switches would feel like, a canonical example would be to refer to Cherry MX Browns as weak tactiles and something like OG Holy Pandas as strong tactiles. It is also worth noting, as well, that I’m using these terms in a relative sense and that there is no hard cutoff line between a binary of weak and strong – tactile strength is a continuous spectrum.

Tactile Bump Size

Figure 3: Range of tactile bump size going from short to wide. (L-R: Cherry MX Brown, OG Holy Panda, Durock POM Tactile, and Novelkeys Cream Tactile)

Tactile bump ‘size’ is the term that I use to describe how much of a switch’s total stroke is taken up by the tactile bump. Intimately tied together with linear pre- and post-travel regions which occur outside of a tactile bump, the bump size can be anything from a “short” or “sharp”, rapid tactile burst to a “wide” or “long” bump which is long, drawn out, and feels like it occupies the majority of the switch’s feeling. Much like with the strength definition above, this too operates on a spectrum from short to wide with there being no particular cutoff in between the two. Unlike the strength spectrum, though, the short and wide ends of tactile bumps are not necessarily created equally. Whereas a long tactile bump may take up the majority of the switch’s entire stroke, short tactile bumps can be located at different points within the downstroke of switch – including at the very start, in the middle, or very rarely towards the latter half of the stroke before bottoming out. (Examples of each of these short bump locations include Zealios at the very start, Cherry MX Browns in the middle, and Gateron Aliaz switches towards the end.)

While these two metrics alone should be enough to clearly communicate the tactility of any switch to someone asking about what the tactility of a switch is like, the real magic comes when you cross these two spectra, considering the tactile bump size as an x-axis and the strength as a y-axis. In this fashion, we end up with four groupings of tactile switches, as can be seen below. Suddenly, the spectrum of tactility from Cherry MX Brown to Holy Panda becomes much more wide and diverse, with Cherry MX Browns occupying the ‘weak and short’ quadrant whereas Holy Pandas are located more so in the ‘strong and wide’ quadrant, but not all the way at the edge of it either.

Filling in the other regions of this tactile switch compass is something that, like all things switch related, simply comes with time and experience with more tactiles of a wide variety. While I wish to stress again that this is not a hard and fast nor perfect system for describing tactile switches, I think that it is a way that could help increase the complexity of how people discuss tactile switches. Instead of switches simply being “more or less tactile”, thinking of tactile bumps in terms of their size and strength relative to baseline provides a more robust description of how a switch feels, is fairly easy to communicate, and is how I mentally categorize tactile switches. And by extension of being incredibly biased in favor of my own opinions, I think you should use this when discussing tactile switches as well!